This is a follow-up article on the question of response times from Nottingham Fire & Rescue. The prior article discusses my efforts to obtain response time data. I requested these data from town administration, but after three weeks in which the request remained unfulfilled, I asked for the data at a public meeting of the Fire Department. These meetings are on the first Tuesday of every month at 7:00 pm at the Fire Station. They are open to the public, but not listed on the town calendar. According to Deputy Chief Mark Pedersen, when I asked for the data at the department meeting no one in the department was aware of my pre-existing right-to-know request for the data.

My persistence in asking for the data at the March 5 public meeting paid off. I was provided with the data on March 20.

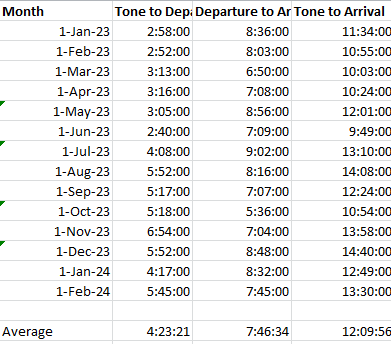

I requested the data to address concerns expressed on Facebook about deterioration in the department’s response times. From this analysis, I conclude:

The data show that response times have indeed become longer, by about 2 minutes, or nearly 20%. The data also show an inflection point between June 2023 and August 2023 during which this response-time increase began.

Understanding the Data

When I was provided with the data, Deputy Chief Pedersen described how the data were collected and pointed out several issues with the data-collection process.

There are several caveats about the data, the foremost of which is that the data are not captured automatically but instead are entered manually. Not only is this process subject to human error, but it is subject to interpretation of what the key variables mean - most particularly, what is it that we’re talking about when we talk about “response time”?

For the general public, “response time” typically means the time between when they call 911 and when first responders arrive at the scene. For fire departments, the subject is more complex, as there are several components to response.

When someone in Nottingham calls 911, the call goes to a dispatch center in Concord. This dispatch center performs initial triage on the call and determines where the call should go next.

In the case of needing a fire or ambulance response in Nottingham, that call next goes to the Rockingham County dispatch center, which then takes responsibility for the call. Rockingham would then contact Nottingham Fire & Rescue to respond. Usually, but not always, Nottingham responds. Sometimes Nottingham cannot respond because it is responding to something else. In that case, Rockingham dispatch retains responsibility for the call and tries to find a neighboring town to respond. Further, for large-scale incidents, Rockingham dispatch may have to get several departments to respond.

For the person calling 911, the clock is ticking, but for Nottingham Fire & Rescue, the clock does not start ticking until they accept the request. The jargon term for this moment is the “tone” — the official signal that the department has taken responsibility for responding.

The next component of response time is the time it takes between accepting the request and departure onto the road. If no one is at the Fire Station, this entails department members coming from their homes or workplaces to the Fire Station. If staff are available at the Fire Station, it usually takes a few minutes to get ready, although sometimes, because staff monitor what’s going on with the dispatchers and neighboring departments, they can figure out that they’re going to be asked to take a call before they’re actually asked to, making it possible in a few occasions for response time to be technically instantaneous because they have taken advantage of this information and are now sitting in the truck ready to go. This can also happen when a truck is on the road returning from an incident.

The final component of response time is how long it takes to get to the scene. Travel times from the Fire Station to points in town vary widely. Getting to someplace in the woods in the state park can take a very long time. The department also responds to mutual aid calls outside of town. These require longer travel times, particularly for large fires involving the fire-fighting resources of many far-flung towns, such as a massive fire in Alton that Nottingham responded to years ago.

The data most relevant to the question at hand is the tone-to-departure time because the location of calls and the condition of the roads are outside the Fire Department's control.

Data Analysis Method

The data are in a software system known as “Red Alert.” The department is required to provide these data to state and federal agencies.

The data set I received was only for calls that Nottingham responded to. It did not include calls in Nottingham that other town’s fire departments responded to. The data were separated into two files, one for ambulance and the other for fire.

Fire calls don’t happen often — only 33 times from January 2023 through February 2024. This isn’t enough to say anything about month-to-month changes over time. I considered merging the two data sets, but the response times for fire were substantially longer than for ambulance. Given how few fire data points there were it seemed that the clearest picture would come from looking only at the ambulance data.

The measures of interest were:

Time from accepting the call (called the “tone”) to departure.

Time from departure from the station to arrival on the scene

Total time, from tone to arrival

The ambulance data had 21 to 39 calls per month. A small number of data points claimed that it took zero time between departure and arrival. As this is implausible, these were removed from the analysis. A few other data points lacked data from tone to departure. These were also removed. In both cases the total time data was similar to that of the data points that were kept. I inspected the data for incidents with travel time that was so large that it might have been for a call outside of Nottingham. I found one so large that I was confident about removing it, although several others might have been to neighboring towns. In total 17 incidents were removed from a total set of 415.

Results

Tone to Departure

Prior to July 2023, tone-to-departure times averaged around 3 minutes. Since then, they’ve been in the range of 4 to 7 minutes.

Departure to Arrival

The departure-to-arrival data showed no pattern, being consistently in the range of 7 to 9 minutes.

Tone to Arrival

Because of the increase in tone-to-departure times, the overall tone-to-arrival times have changed over time. From January to June 2023 they were in the 10 to 12 minute range. Since then they have been in the 13 to 14 minute range.

So, the data corroborate the concerns expressed on Facebook. Response times have increased.

Response times, however, did not increase following former Fire Chief Jaye Vilchock’s being put on paid administrative leave in March 2023; they increased following the departure of Interim Fire Chief Dale Sylvia in June 2023. This, of course, may just be coincidental to changes in staffing during these periods. My right-to-know request did not include a request for the staffing data needed to draw further conclusions about the increase in response time.

The data I was provided with did not include a variable regarding whether the first responders were at the Fire Station or were responding due to being on call. The longest tone-to-departure time was 58:49. The second longest was 52:40. The third was 39:44. 21 responses took more than 15 minutes. 33 took more than 11 minutes.

Taxpayer Concerns

Not only do response times matter to those in need of help, taxpayers are rightly concerned about whether their taxes are giving them what they were promised.

In 2022, the voters approved a warrant article to add three full-time staff to the Fire Department at a cost of $225k/yr, which is surely higher now due to wage increases to keep up with inflation. In 2022, this was $0.092 per $1,000 per assessed valuation.

In the 2022 voters guide published by the Board of Selectmen, the board said:

This article would provide funds to add career firefighters to the permanent staff and allow the department to staff the station 24 hours/day. The Town currently relies on an On-Call ‘volunteer’ force to respondduring evening and overnight hours.

This expanded coverage is expected to provide for faster response times; improved employee retention; and reduced dependence on the On-Call force.

Average Response Time in 2021 during hours the station is staffed: 8 minutes, 14 seconds

Average Response Time in 2021 when members had to respond from home: 20 minutes, 26 seconds.

The interest and ability of residents to “volunteer” to work as part of this Call Force continues to drop over time, and the demand for services continues to increase.

Calls for Service, 2021: 672

Calls for Service, 2011: 435

Career firefighters can work in many NH cities and towns, and Nottingham has struggled to retain qualified personnel in many cases because the work schedule offered with 24-hour departments is preferable to employees.

This step to 24-coverage is the next step in a long-planned evolution, with the increases in the town’s population and service expectations. Last year, voters approved funds for renovating the station to provide bunks for 24-hour staff.

One point Deputy Chief Pedersen emphasized to me was that it was mathematically impossible to staff the station 24/7 with two people out of a full-time staff of six. This claim appears to contradict what the board told the voters in 2022.

Let’s do the math.

The first issue is what defines “full-time.” In the private sector that would be 40 hours per week. That rule doesn’t apply to firefighters and police. Federal law allows them to work 53 hours a week before being eligible for overtime.

Municipalities are free to set their own rules for overtime so long as they do not conflict with Federal law. As previously reported, one of the conflicts between the town’s former Interim Town Administrator and its former Fire Chief was about how overtime was being handled at the Fire Department, with the Interim Town Administrator blaming the Fire Chief for the Fire Department not operating according to the written overtime policy of 45 hours and the Fire Chief saying that with the adoption of the 2022 warrant article the Board of Selectmen and the former Town Administrator knew the new staffing plan for the department and had agreed to it and it was their failure to update the written policy to match the new agreed-upon practice of 48 hours.

Full-time firefighters typically work in 24-hour shifts. Two shifts per week equals 48 hours; hence a 48-hour standard workweek. Two employees are needed for coverage. Therefore six full-time staff can provide coverage 24/6 — that’s six days per week, not seven. Add to that vacation and sick days and it’s less than six days per week. To achieve 24/7 coverage with six full-time staff requires either overtime pay or some per diem staff – which the department has – necessary for covering the days the full-time staff can’t cover. Assuming that for various reasons the full-time staff are off 20 days per year, that plus 52 is 72 days that must be covered by per diems or a lot of overtime pay.

So, whether the math “works” is a function of the definition of “works.” It doesn’t work for six full-time staff without lots of overtime. It works without overtime for six full-time staff plus about 3,500 hours a year of per diem staff – less than two full-time equivalents.

This assumes being fully staffed. Between voluntary and involuntary departures, the Fire Department has been chronically understaffed since March 2023. All understaffing must be filled in with either per diems, or overtime, or leaving the station unstaffed and relying on on-call members – the traditional volunteer fire department method, but which adds to the response time.